Home Lesson-5.3

Lesson-5.2

Lists

Mutability

Consider the following problem:

Assume that you work at a company that analyzes cricket matches. As a part of the data collection process in the IPL, the data-processing team is tasked with recording the runs scored in every ball in every match. It is your colleague's turn to do the bookkeeping for the final match between CSK and MI. Just before the start, the "0" key on his keyboard stops functioning. As a workaround, you cleverly suggest that he use the letter "O" instead of 0. Once the match is over, you collect the list of runs scored. Write a program that replaces all appearances of the letter "O" with the number 0. I leave it to your imagination to decide who won the finals!

Solution

xxxxxxxxxx61runs = [1, 4, 2, 'O', 4, 'O'] # the data for one over is given here2print(runs)3for i in range(len(runs)):4 if runs[i] == 'O':5 runs[i] = 06print(runs)The most interesting line is the fifth one: runs[i] = 0. We are updating a list in-place. Python permits this operation because lists are mutable. Contrast this with strings that are immutable, which means that they cannot be updated in-place. Mutability makes lists powerful; but reckless exercise of power always results in instability as is demonstrated by this notorious example:

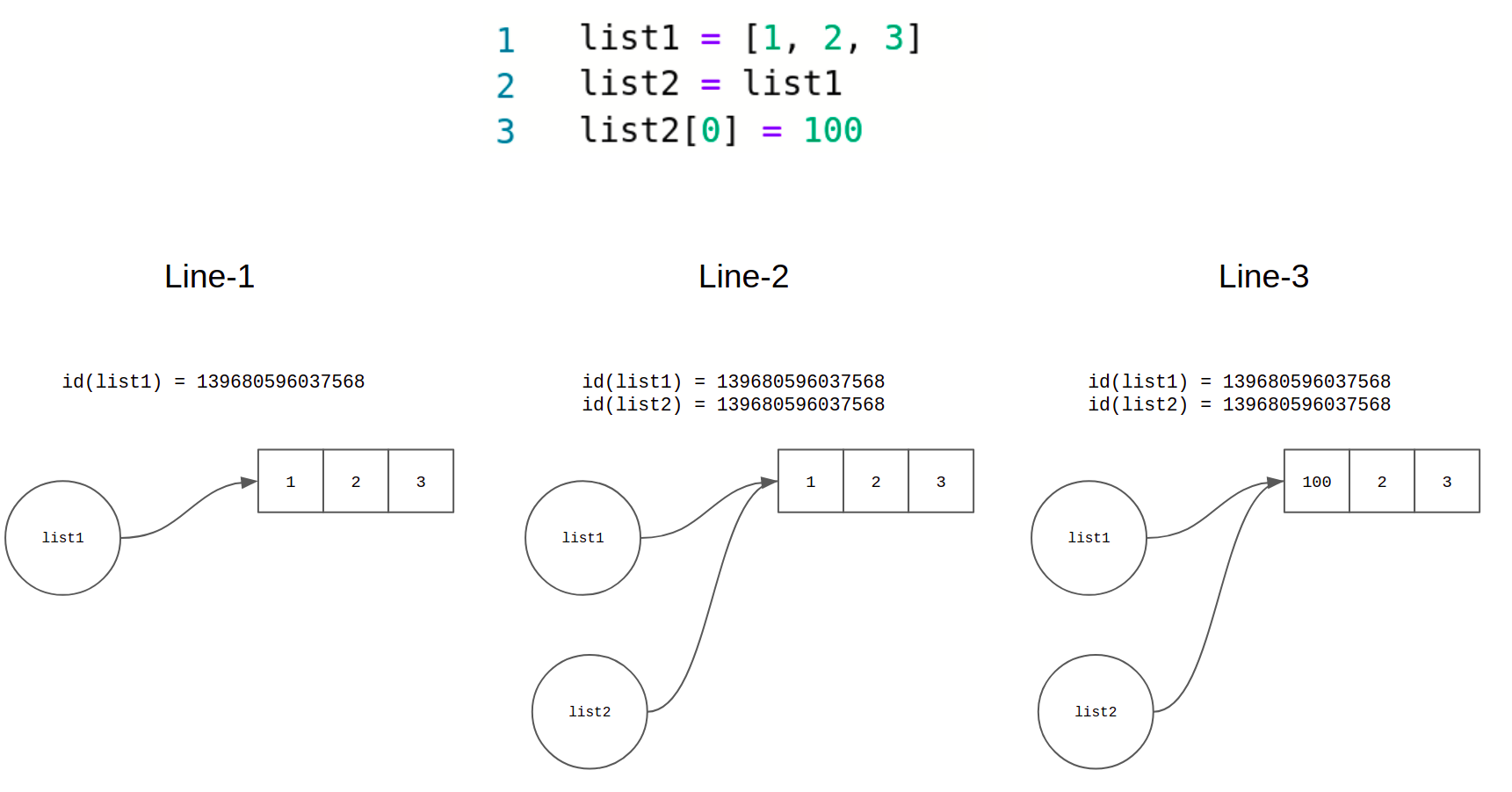

xxxxxxxxxx51list1 = [1, 2, 3]2list2 = list13list2[0] = 1004print(list1)5print(list2)Both give the same output even though we are only modifying list2 in-place!

xxxxxxxxxx21[100, 2, 3]2[100, 2, 3]

What is happening here? To understand this, we will take the help of a built-in function called id. Every object in Python has a unique identity: if x is an object, then id(x) returns this object's identity. From the Python documentation, "this is guaranteed to be unique among simultaneously existing objects". In the implementation of the Python that we use, this unique id is nothing but the object's memory address.

In line-2, we are not creating a new object. We are merely creating another name, also called an alias, for the same object. Think of this like having a nickname. Your name and nickname are two different words, but both of them refer to you. To see if two Python names point to the same object, we can use the is keyword:

xxxxxxxxxx41list1 = [1, 2, 3]2list2 = list13list2[0] = 1004print(list1 is list2)This prints True. Now consider another scenario:

xxxxxxxxxx41list1 = [1, 2, 3]2list2 = [1, 2, 3]3print(list1 == list2)4print(list1 is list2)This gives the following output:

xxxxxxxxxx21True2False

This because equality and identity are two different things. In the code, line-3 checks for equality of two lists, line-4 checks if the two lists point to the same object. list1 and list2 point to two different objects and consequently have different identities. But, they store the same sequence of items and are hence equal.

How do we create a copy of a list so that updating one doesn't end up changing both? Python provides three ways to do this:

xxxxxxxxxx111list1 = [1, 2, 3]2list2 = list(list1)3list3 = list1[:]4list4 = list1.copy()56list2[0] = 1007list3[0] = 2008list4[0] = 300910print(list1, list2, list3, list4)11print(list1 is not list2, list1 is not list3, list1 is not list4)This results in the following output:

xxxxxxxxxx21[1, 2, 3] [100, 2, 3] [200, 2, 3] [300, 2, 3]2True True True

- In line-2, we pass

list1as an argument to thelistfunction which returns a new list object with the same sequence of elements aslist1. - In line-3, we are slicing the list. Slicing a list results in a new list object. As no

startorstopvalues are mentioned, they are going to default to0andlen(list1)respectively. So, the entire list is returned. However, it is a brand new object. - In line-4, we use a method call

copythat is defined for thelistobject.

Lines 10 and 11 verify that the methods used to copy lists in lines 2, 3 and 4 actually work.

Call by reference

Mutability impacts the way lists are handled in functions. Consider these two snippets:

xxxxxxxxxx81# Snippet-12def foo():3 L.append(1)4 5L = [0]6print(f'L before: {L}')7foo()8print(f'L after: {L}')Snippet-1 doesn't have any parameters. Since L is not being assigned a new value inside foo, the scope of L remains global.

xxxxxxxxxx91# Snippet-22def foo(L_foo):3 L_foo.append(1)4 print(L is L_foo)56L = [0]7print(f'L before: {L}')8foo(L)9print(f'L after: {L}')Snippet-2 has L_foo as a parameter whose scope is local to foo. But note that modifying L_foo within the function changes L outside the function. This is because, L_foo and L point to the same object. How did this aliasing happen? The function call at line-8 works something like an assignment statement: L_foo = L, so L_foo is just another name that refers to the object that L is bound to. This type of function call where a reference to an object is passed is termed call by reference. Whenever a mutable variable is passed as an argument to a function, the references to the corresponding object are passed.

If all this seems too complicated, just remember that modifying mutable objects within a function produces side effects outside the function. What if we don't want these side effects? We have to create a new list object like we did before:

xxxxxxxxxx81def foo(L_foo):2 L_foo.append(1)3 print(L is L_foo)4 5L = [0]6print(f'L before: {L}')7foo(list(L))8print(f'L after: {L}')foo doesn't produce any side effects. Line-7 could be replaced with foo(L[:]) or foo(L.copy()).